Good evening.

Before we get into this week’s update, I wanted to thank readers who wrote in or spoke to me after last month’s Issue 2: Portugal is the New West Coast. While most were kind in agreement and glad to see more attention on Portugal, a few pointed out additional considerations on the ground.

First, despite publicly stated intentions at the top for an entrepreneur-friendly environment, not everyone in the government seems to have gotten the memo. Bureaucracy doesn’t always match the rhetoric. A reader pointed me to this recent tweet by Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince:

Prince submits for evidence demand by Portuguese agencies that Cloudflare create more than a hundred high-paying engineering jobs in Portugal in 12 months from scratch in the middle of the pandemic. I’ve built many technical teams in my career, and this seems a frustratingly tall order indeed.

Another reader pointed out that taxes were exorbitant regardless of a business’s profitability. And, the abstruseness of the tax code adds further burden to the entrepreneur. That said, somewhat unexpectedly, readers who were small business owners did not mind at all lobbying by large multinational companies. That’s because rather than individually negotiated concessions, the lobbying efforts have aimed at improving the rules to benefit everyone.

Yet another reader, based in Berlin, summarized the dissenting sentiment best: Portugal’s brand for startups may have peaked. I appreciate the sentiment based on the level of concerns I’ve heard, but believe we are actually still on the front end of how Portugal will shape up itself. Taking European geography and demography into account, there isn’t much elsewhere in Western Europe to go where startups can still find high-quality, English-speaking talent and where the cost of living is significantly lower. That said, facts on the ground, as always, are more nuanced and Portuguese policy makers do seem to have much work cut out still. Here, the Singapore Economic Development Board, enthusiastically embraced and applauded by foreign investors in the city-state, may provide a helpful reference point for their Portuguese counterparts.

Lastly, a reader based in Lisbon wanted it be known that in the midst of the pandemic, Portugal was kind and protective of its residents, regardless of their citizenship.

Bureaucracy is painful here but if a real emergency happens it is nice to know that the government will try to help the people who are here.

I cannot express enough how grateful I am for these reader comments, and I look forward to our future exchanges.

Now, onto today’s update.

1.

For those that work with wood, especially by hand, the name George Nakashima (中島勝寿) evokes a special kind of reverence. Born in Spokane, Washington in 1905, Nakashima embodied rugged American ingenuity and master craftsmanship. He lived an understated yet illustrious life that started by the mountainous timberlines of the Pacific Northwest. His studies and apprenticeships took him to Paris, Tokyo, and Pondicherry. Later he planted roots in Pennsylvania and there built a home, studio, and workshop that would become a mecca of contemporary American design.

As an Asian American, I see in Nakashima an earlier generation of elders who, embracing both their American identity and Old World heritage, were bound by neither and became something more. Nakashima’s Bucks County estate has been designated a National Historic Landmark and listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. In 1983 he received the Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Emperor of Japan. Today Nakashima is widely considered a father of the American Craft movement and one of Twentieth Century’s most important furniture designers.

But Nakashima also likely shared sidewalks and restaurants with his fellow Americans in post-World War I France such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein. Arriving in Paris for his university studies in 1928, Nakashima’s best friend was a Russian composer and aristocrat, yet he admired the simplicity and sedulousness of the French workmen. As a French speaker, I was delighted that Nakashima was also and that he took quiet pride in his linguistic command to “almost joke like a native.” He was mesmerized when his menial theatre job brought him in close personal contact with grand European singers at the time such as Raquel Miller and Josephine Baker, who were the toast of Paris.

Like many Japanese Americans of his generation, during World War II he was imprisoned, along with his wife and newborn daughter, in an Idaho concentration camp. A stoic patriot, Nakashima spent hardly half a page on his time in Idaho in his 1981 autobiography The Soul of a Tree, and even then, he focused on his work:

[I]n Idaho I met a fine Japanese carpenter trained in Japan along traditional lines…We worked well together, scrounging in scrap woodpiles for bits of lumber. Sometimes we received permission to go out into the desert of central Idaho to find bits of bitterbrush, a brave shrub of great character which grows only a few feet in a hundred years. I learned a great deal from this man, through his hundreds of small acts of perfections. He helped me with many of the basic woodworking skills — for instance the correct sharpening of a chisel. We used a traditional Japanese waterstone, which if handled well can produce the finest of edges... He also taught me to sharpen a Japanese handsaw with its very deep gullet. The Japanese saw not only has saw teeth, but below each tooth, a further deep recess which takes away the sawdust without clogging.

2.

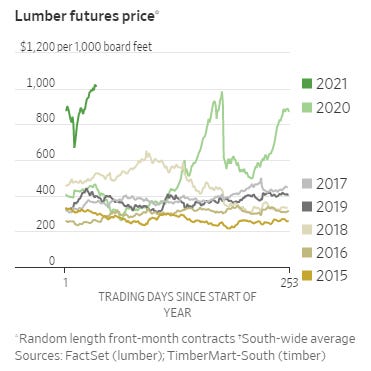

In this week’s Wall Street Journal, a headline caught my attention: Lumber Prices Are Soaring. Why Are Tree Growers Miserable? The context is the current remodeling and construction boom. More people are working and schooling children from home, and restaurants are building new outdoor spaces to adapt to the pandemic.

But it turns out tree growers aren’t benefiting from this demand surge. That’s because before the trees can be used by construction workers, they first must be processed by sawmills, which are at full capacity. Doubling the woes is a poorly-timed oversupply of trees in the market. So even as builders pay top dollar for wood, sawmills are buying trees at historic low prices. The Wall Street Journal report estimates that log prices, after adjusting for inflation, are at their lowest in more than 50 years.

For an investor, the first and most obvious lesson is the importance of industry-level value chain analysis. To the uninitiated analyst, it is all too easy to conclude that strong demand for “wood” would drive up prices, tempered by ample supply. This would have been a boring, and wrong, assessment of value creation in the forestry sector: a critical segment in the industry value chain, the preparation of log so it becomes lumber, is missing.

But sharpen our chisel and we find hidden lessons to be joined. For example, how did the sawmills garner so much market power? The first-order answer is that a few sawmills have consolidated most of the capacity, but what made it economically attractive for them to do so in the first place?

In Nakashima’s time, logging down a tree, examining it, and deciding its cut was a spiritual journey. In Nakashima’s words:

There are so few who listen to the inner voice. In ages past, it would have been easy to join a crusade, to become a member of a community dedicated to building a great cathedral, to hew the great timbered doors, to carve a spirit in stone to grace the glorious façade.

But one must work alone, building objects of wood. With a mendicant’s eye, a sadhu’s perception, a ragpicker’s sense, I poke my way through the valley of the fallen giants, finding here and there fragments which will be given a second life.

While few commercial mills practiced Nakashima’s philosophy even during his time, the process to prep logs into commercial lumber was, for a long while, mostly the same regardless of the size of the tree. As such, older trees fetched top prices as their girth made possible wider panels that looked magnificent alone or joined by butterfly locks.

But automation advanced, and fitting the machine to the most common girth not only brought down the unit cost but made older trees undesirable. From the Wall Street Journal article:

When Interfor arrived, it studied the surrounding trees, noting ages and diameters, then calibrated mills to accommodate the most common-sized trunks..

There aren’t enough of the oldest, thickest trees to justify scaling mills for them. Many of the biggest trees went from fetching top dollar to being mashed into paper and cardboard for much less money.

Something else also happened:

Because of trees bred to become planks and the computerization of mills, well-managed timberland produces about 50% more wood than it did a generation ago…

In other words, through product standardization the mills commoditized logs even further. It mattered not where trees came from. No, these planks would never attain the exquisiteness of parcels expertly air-dried and handpicked by Nakashima and his compatriots, but mills competed even less than before on supply and instead on the buyer experience. For example, Canfor, one of the major mill operators mentioned in the Wall Street Journal, has invested heavily in digital transformation with a focus on real-time supply chain visibility for the customer.

In his 2003 book The Innovator’s Solution, Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen anticipated the above shift:

Formally, the law of conservation of attractive profits states that…when modularity and commoditization cause attractive profits to disappear at one stage in the value chain, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage.

Said plainly, what’s happening in forestry is no different than that in publishing. Much as Google and Facebook commoditized content and disaggregated writers and publishers from the audience, advanced automation and standardized plank production allowed mills to disproportionately disrupt the economics of forestry.

But the story doesn’t end here, at least not if you care about the longer-term outlook of all this technological change and economic activity.

3.

Thea Snow, Director at the Centre for Public Impact, Australia and New Zealand, recently penned a column calling for governments to engage with the complexity in our natural world and think more systematically when making policy. By way of example, it turns out the modern tree grower’s decision to plant neat rows of one species of fast-growing trees severely misunderstands the mycorrhizal effect, among other relationships, between trees and the forest floor.

For the first generation of trees, the agriculturalists achieved higher yields, and there was much celebration and self-congratulation. But, after about a century, the problems of the ecosystem collapse started to reveal themselves. In imposing a logic of order and control, scientific forestry destroyed the complex, invisible, and unknowable network of relationships between plants, animals and people, which are necessary for a forest to thrive.

ESG measurements (environmental, social, and corporate governance) are rapidly gaining currency today because in a post-COVID world investors better appreciate the importance of a company’s sustainability and societal impact in determining the company’s financial future. Yet one must resist the urge to find quick, seemingly scientific answers. In his book Analogia: the Emergence of Technology Beyond Programmable Control, historian George Dyson proposes that any system simple enough to be understandable will not be complicated enough to behave intelligently, while any system complicated enough to behave intelligently will be too complicated to understand. Such stipulation is reason enough to operate as if our current knowledge were wrong, and to view our journey to better understand sustainability as trying to be less wrong.

In the epilogue of his autobiography, Nakashima demurs:

In a personal way my family and I have gone underground, since we have little relationship to contemporary mores, institutions, economy or systems.

As COVID has taught that we tend to underestimate tail risk and misinterpret false simplification of a complex world for the world itself, let us hope Nakashima’s humbler and more spiritual approach makes a return and helps guide our pursuit for a prosperous yet ever more enlightened human existence.

If you enjoyed this update, please consider forwarding to a friend or subscribing by clicking on the button below. Thank you for your support.

From Aspen, Colorado 🇺🇸

Victor

Share this post